Advanced Manufacturing For Diesel Racing

This article was published by Rober Schoenberger on December 7, 2016 in TodaysMotorVehicles.com

Haas machines allow racing components manufacturer Fleece Performance Engineering to expand, insource parts, and push the limits of how much power a diesel engine can produce.

_fmt.png)

It didn’t start out as a manufacturing business.

At first it was a dream – a ridiculous, insane, completely irrational dream. Brothers Brayden and Chase Fleece just wanted to see a 6,000 lb diesel pickup cross a quarter-mile drag race finish line in 9 seconds. So they started playing with components, altering fuel systems, placing oversized performance gear on engines, tinkering in their Indiana garage.

“It started out with us just having our own personal truck. We bought a few parts that performed OK. They satisfied our horsepower addiction for a short period of time,” says Brayden Fleece, co-founder of racing equipment manufacturer Fleece Performance Engineering. “It eventually got to where we were modifying the turbos and fuel systems. Pretty soon all of our friends wanted things done to their vehicles, so we started bolting things onto their trucks. It pretty quickly became our full-time job.”

Like most performance tinkerers, the Fleece brothers focused on getting more to the engine – more fuel and more air so the Duramax engine in their Chevy pickup could produce more horsepower.

“Everything had its design purpose. My 2004 Duramax has a specific output of 305hp, and that’s what they designed the turbo to do,” Brayden says. “We took some parts from a different parts bin and made them fit inside the turbo from the Duramax. We made it move more air. By having that identical-looking turbo, that bolts on just like it did when you took it off, you had 200hp more to the wheels than you had before.”

Initially, they were able to fit larger turbo wheels inside the old housings, but after a few years, they hit the limits of what they could do with other peoples’ parts. To get more power, they would have to build parts themselves.

CNC needed

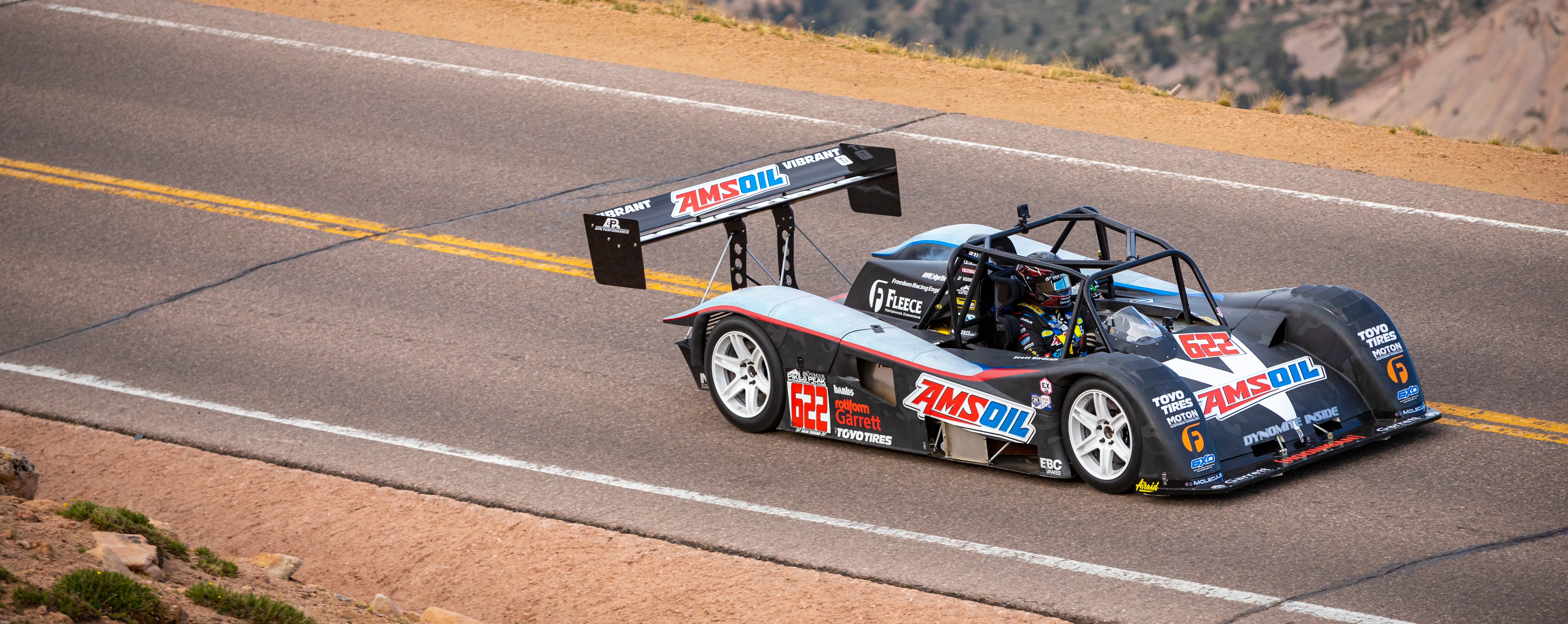

Diesel trucks sporting Fleece Performance Engineering turbochargers and engine modifications prepare for a quarter mile drag race. Indiana-based Fleece has purchased several Haas CNC tools throughout the past four year, giving the company the opportunity to insource many of its components.

Chase Fleece explains that eventually, the turbocharger wheels that he wanted to use were too big for the stock housings, so he had to create more space in the cast iron housings.

“It was kind of a Frankenstein of lots of different turbo components that weren’t supposed to fit together,” Chase says. His brother adds that the early models of their custom turbo were tough to produce.

“There was definitely a need for a piece of CNC equipment at that point, but we didn’t have one. We had a 1940s South Bend lathe with a leather drive belt at a friend’s welding shop,” Brayden recalls. With limited machine clearance, he had to make several angle cuts into the housings and knock down the walls to create space. Between all of those cuts and hours of hand finishing, each turbo required nearly a week of machining time to finish. After producing about 30 on that equipment, the brothers bought their first Haas CNC lathe, a TL-1, in 2008.

With the computer-controlled equipment, machining the turbo housings went a lot faster. Brayden says he simply had to figure out the radii of the turbo wheels, add a bit of space for clearance, and program that number into the machine. Within weeks of getting the lathe, Fleece Performance went into full production on race turbos for diesel trucks.

Chase adds that ideally, Fleece Performance would have designed its parts on CNC equipment, but during those prototyping days, “We were young and didn’t really know the ins and outs. But we were determined and had a machine that could do the work, so we sat down and made it work. Once we bought the Haas, the gates opened up for us. We were able to make a bunch of different types of turbos.”

Instead of focusing only on the turbos used for General Motors’ Duramax diesels, the brothers turned their attention to the Cummins engines used in Dodge Ram diesels – a popular option for drag racers and competitive truck pullers.

Fleece Performance Engineering got its start by packaging components from various turbochargers into a large housing. It has expanded by machining its own housings and turbocharger wheels.

Reinventing the wheel

With better equipment, Fleece Performance’s ambitions rose. Instead of cobbling together stock parts from multiple suppliers and machining a housing that could fit it, the company started ordering custom turbo wheels so they could optimize performance for a wider range of racing applications.

“Truck pulling drives our turbo development. Every size class in pulling has specific limits of turbocharger sizes. So we started making turbochargers to fit the rules for every size class,” Brayden says. To get more compressed air into the engines, he says Fleece maximizes the blade surface areas of the turbocharger wheels while minimizing the shaft sizes.

“You’d never see Cummins or GM do something like this. Their turbos are designed to run for 1 million miles. Ours are designed to win races,” he adds.

Until about four years ago, the Fleece brothers were able to get those custom-designed turbo wheels from another manufacturer, allowing their company to focus more on housings and system packaging. But when their supplier went out of business, they decided to bring turbo wheel machining in house.

Freedom Racing Engines

There’s only so much boost you can get from an optimized Fleece Performance turbocharger before you exceed an engine’s ability to contain combustion. So, in 2014, the Fleece brothers founded Freedom Racing Engines, a company that modifies diesel engines and creates its own blocks.

To modify Cummins diesels, Freedom engineers use a Haas VF-6/50 vertical machining center, setting the block in the fourth axis in a rotisserie setup.

“We bore the block, deck it, drill and tap the head studs and main studs, changing them over to a larger stud, all in one operation,” says Chase Fleece, co-owner of Freedom Racing Engines. After boring out the cylinders, technicians insert ductile cast-iron sleeves that can handle significantly more pressure than the base engine block. Chase adds, “That was a really good business case. It took 40 hours, just in machine time, to prep those blocks for our sleeves. Now it takes four or five hours.”

Though the sleeves reduce engine displacement – the base Cummins is 6.7L, but after boring the cylinders and inserting sleeves, the finished engine is only 6.4L – the cylinders can accept higher turbocharger boost levels.

“You contain all the cylinder pressure in the sleeve, so the block is not required to hold nearly as much pressure,” Chase says. “A block that was typically split down the middle at 1,200hp to 1,300hp will now support up to 2,000hp, and we’re still pushing the limits. We haven’t had a block split yet after we put sleeves in.”

Co-owner Brayden Fleece adds that for racers who want to push the performance envelope further, Freedom Racing plans to machine its own versions of the Cummins block from a 900 lb aluminum billet.

“When you get to that 3,000hp mark on a Cummins, even with the sleeves, the engine will separate,” Brayden says. With a custom-machined version of the engine, he adds that Freedom should be able to cross that power threshold. www.freedomracingengines.com

Shop expansion

Adding turbo wheel production required buying several vertical machining centers and other equipment. Fleece employees blank the forged turbo wheels on a Haas DS30SSY dual-spindle lathe. Chase says when the brothers bought the lathe, it was a turnkey system. They took the wheels they needed to machine to their Haas representative, Coby Smith of HFO/Chicago, and asked for the machine that could do that job.

The wheel-machining system also includes a VF-2YT vertical machining center (VMC), a 3-axis, 15,000rpm machine equipped with a trunnion table to provide a fifth axis.

After technicians blank the turbo wheels on the lathe, the VMC cuts the blade profiles. Between the two machines, Fleece technicians can produce a custom turbo wheel in about 75 minutes.

Within a couple of months of getting the new equipment in house, Brayden says the brothers realized they were holding themselves back by not having any available spindle time for new work or prototyping.

“When you sit back and amortize the product that you’re making, what it generates in revenue, what the machine payment is, the operator, the lights, all of your overhead, having that second spindle running parts in parallel makes a lot of sense,” Brayden says when explaining why Fleece opted to buy multiple VMCs. “It also lets us prototype more. If you only have one VMC and you need to prototype a bracket or some simple part, you can’t do it if you’re running production on all of your spindles.”

About four years ago, the brothers started producing parts with one Haas CNC machine. They now have eight.

“I never imagined that within four years of moving into this shop, we’d have a 5-axis here or a dual-spindle lathe with live tooling,” Brayden says. “We’re not machinists. We weren’t running a machine shop. But once we got a taste of machining our own turbos, that changed everything. We heard a few too many times that something couldn’t be done. We’re a couple of farm kids, and we’re willing to stick with something until we get what we want.”

Efficient operations

Chase Fleece (left) and Brayden Fleece (center) show off their largest vertical machining center, a Haas VF-6/50, with Operations Manager Jeff Merriman (right).

A key to success in racing production is fast turnaround, Brayden explains.

“We’re in a wants market. Nobody really needs anything that we make, so we can’t afford customer shipping delays,” Brayden says. So as Fleece has expanded, it has put a premium on equipment uptime and reliability.

Chase adds that the relatively low cost of the Haas equipment has allowed Fleece to expand quickly and produce more of its own parts. Having a vertically integrated supply chain makes it easier to plan production and ensures on-time delivery to racing customers.

“The price point is right. They’re not cheap machines, they’re well valued,” Chase says. “We do a lot of development that doesn’t generate profit any time soon. We’re constantly buying new vehicles and testing new parts. We couldn’t afford to do that if we were investing all of our revenues on new equipment.”

Some of those development projects include a diesel Chevy Colorado light pickup and a diesel Chevy Cruze compact car – a vehicle the brothers have been able to boost to 250hp and 350 lb-ft of torque, up from the base 2L’s 151hp and 264 lb-ft. And it gets 52mpg in highway driving.

“I don’t know if there’s a market for racing that one yet, but we’re playing with it,” Chase adds.

Brayden says investing in Haas machines is “about making money. We want to make good parts with the least amount of overhead as possible. People like to talk about expensive machines, but we have no issues with our Haas machines. Our parts are dimensionally accurate. Our uptime is up around 95%. They do a good job. They do everything that we ask of them. They’re easy enough to use that my brother, the hammer swinger, can step up and use the lathe.”